From a fisheries perspective it is very frustrating to watch the marine protection cum reserves debate occur without any intention to address the root causes of depletion – excessive fish catches, mobile bottom contact harvesting methods degrading habitats, and contaminants entering waterways choking nursery areas.

LegaSea supported the recent submission by the New Zealand Sport Fishing Council in response to the Government’s Marine Protected Areas (MPA) Act proposals.

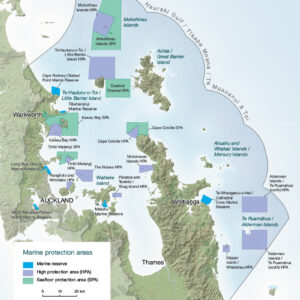

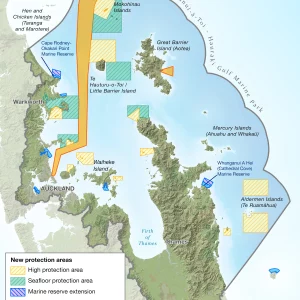

Highlighted in the submission is the need for a more integrated approach to marine protection, with different marine protected area categories to meet the specific environmental needs of an area, while taking into account existing and future values and uses.

We submitted that there was a risk in people interpreting the Government’s objective as an intention to set aside 10% of the Territorial Sea, out to 12 nautical miles, in no-take marine reserves.

It is not clear how an arbitrary figure of 10% would work in each region, but setting aside 10 percent of coastal and marine areas would have a significant effect on all fishers.

What’s more, there is a clear need to consider other categories of marine protection to enable other uses of marine waters, including non-bottom contact fishing methods such as trolling for marlin and tuna, which has minimal impact on biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Downstream effects of MPAs

Any proposal for an MPA needs a clear purpose and a risk assessment; to ensure that the downstream effects of a marine protected area does not nullify the perceived gains. Creating a domino effect with displaced fishing effort from protected areas is very real.

For example, as new no-take marine reserves are established fishing will be displaced, often into neighbouring areas, with potentially disastrous consequences for abundance, biodiversity and ecosystem services in those areas. This outcome would contravene both the UN Convention to conserve biodiversity, and the government’s objective to enhance, protect and restore marine biodiversity inside and outside protected areas.

In the MPA proposals there was no mention of how displaced fishing effort will be managed. The frustration lies in the failure to acknowledge that the cumulative effect of MPAs will require catch reductions for some species, or method restrictions in certain areas.

The economic and biodiversity risks also need to be considered, as does the social impacts of serving one community’s aspirations at the expense of another’s access to healthy fisheries and marine biodiversity.

It is strange that no-take marine reserves are directed at biodiversity threats yet there is no process to either identify threats or consider mitigation options to address those threats.

In our view, the best protection for biodiversity is to restore abundance across the entire inshore ecosystem while directing scarce biodiversity resources to protect species and habitats known to be at risk.

If the government is serious about restoring abundance, protecting marine biodiversity and ecosystem services it needs to start applying the sound environmental principles already included in the Fisheries Act.

Ultimately, no-take marine reserves can be part of a restoration programme for New Zealand’s inshore marine ecosystems, but promoting them as the main defence against the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services is delusional.