Collecting kai moana is a Kiwi summer tradition, wading in knee-deep water, collecting buckets of pipi, cockles, or whatever else your auntie fancies. It’s an ancient practice, and a way of life for some.

Running out of hands to collect used to be the norm. Instead, we are faced with emergency closures and rāhui, temporary closures, as a response to combat our declining shellfish stocks.

Once, not that long ago, our intertidal flats were abundant with edible shellfish, now they’re a victim of environmental stresses and over harvesting.

Rising human populations comes with consequences. Sewage, sediment, and land run off to name a few.

Estuarine ecosystems can support rich ecosystems when healthy and productive, but as environmental pollutants suffocate our estuaries, shellfish become the inevitable casualties of these environmental stresses.

When climate change and overfishing join the equation, we witness a less resilient ecosystem, susceptible to collapse.

If collecting and eating shellfish are becoming a scarce reality, we can assume similar effects on juvenile fish and other marine organisms. Coastal fish may be adaptive as they can feed on a variety of different food, but at what point will they be left to starve?

The scientific analysis linking ‘mushy-fleshed’ snapper in the Hauraki Gulf to chronic starvation is a stark reminder of the urgent need for action.

Without shellfish in intertidal estuaries, coastal juvenile fish will have to move elsewhere and into deeper waters to find food, increasing their vulnerability.

Concerns are growing among iwi and hapū as mussel, cockle and other shellfish populations are diminishing. For centuries, shellfish gathering sustained Māori communities. Now, depletion is depriving people of the wellbeing generated from learning and sharing in those cultural practices.

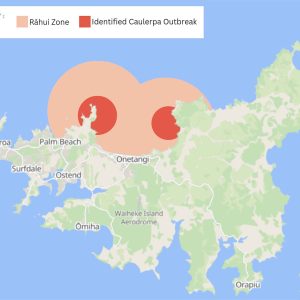

Many Hauraki Gulf beaches now have rāhui in place to prevent shellfish harvesting, often initiated by proactive communities in the absence of government action.

Ngāti Manuhiri demonstrated their commitment to their role as mana whenua, by imposing a two year rāhui around their rohe moana. With the aim of restoring scallop populations for generations down the track.

The marine environment is pleading for better protection. A healthy environment is essential for healthy fish and well-fed people.

While we can’t control ocean temperatures, we can advocate for our local councils to take effective action to reduce sediment and run-off from entering our waterways.

Shellfish beds need a chance to breathe. We must act now if we want to restore the food basket for those who come after us.