Recreational perspective on shared fisheries and developing trust

Address to the Seafood New Zealand Conference.

Grant Dixon, Editor. New Zealand Fishing News magazine.

Thank you for the opportunity to give my perspective on the fishery and building trust between industry and the public/recreational fishers. When Tim Pankhurst contacted me and explained the brief, I was a little nervous. Daniel in the lion’s den came to mind. Then he promised a seafood dinner to die for and like the mouse tempted by the cheese, the trap was sprung!

To my mind there are five recognised players in this fishery – there is the likes of myself – recreational fishers; the commercial fishers on the water – in particular, those leasing quota; customary Maori; the big corporate quota holders; and the politicians/Ministry. Not all have been born equal. The single most important player receives almost no recognition – and that is those who will follow us – our grandchildren and their grandchildren.

I like to think the rec fishers have the most in common with the commercial guys leasing or with small quota holdings. They are heavily dictated to by the Ministry and the corporates as to the outcome of their fishing. Customary fishers have the Treaty of Waitangi to fall back on so they are always going to be well catered for – more or less. Most Maori fish under recreational rules anyway, so in the main Maori are lumped in under our umbrella.

Please note at this stage I have not mentioned the word ‘shared’ in relation to the fishery, because I don’t believe such an animal exists, not from where I stand, not yet anyway. There are deepwater fisheries, inshore fisheries, pelagic fisheries, depleted fisheries, screwed fisheries, but nothing that is truly a shared fishery.

My Collins dictionary defines ‘share’ as ‘to divide or apportion, especially equally’. I can’t see where that currently applies to my interest in the inshore fish stocks, the only ones I am interested in. How many of you grew up with siblings and when it came time to share a cake, pie or a piece of fruit, the rule ‘You Cut and I Choose’ was used to determine a fair share?

From a recreational perspective, that hasn’t happened in our fishery. To me, a ‘shared fishery’ in the industry context means an everlasting constraint on non-commercial fishers. Shared fishery is a construct to frame a discussion – if we are going to move ahead together it needs to be put aside.

In the past any Ministry proposal for a ‘shared fishery’ always contains provision to ring-fence the recreational catch, making no allowance for a growing population. Some of its earliest attempts at creating proportional share resulted in the public formation of option4. The ministry tried to hoodwink the public into choosing one of three options, all of which were proportional share in one guise or another and we didn’t buy it.

The ‘fourth option’ has since morphed into LegaSea, the NZ Sport Fishing Council’s public advocacy arm. It was probably the best thing the then Ministry of Fisheries ever did for recreational fishing as it began a unification of that sleeping political giant – the fishing public.

While there are all sorts of figures bandied around, the ministry accepts that around 20% of the population fish. Add to this the 108,000 tourists who fish here every year, and you have a fair bit of clout, in terms of both votes and dollars generated. In the interests of moving forward, I don’t intend playing the blame game. But if we ignore history, we run the risk of repeating its mistakes.

You will most likely be familiar with the book by the late David Johnson, completed by Jenny Haworth – Hooked – the story of the NZ Fishing Industry. It is a fascinating insight into the development of commercial fishing and its players, I thoroughly enjoyed it. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always paint the industry in a good light.

Starting with the sealers and whalers, who after Maori were the first traders to exploit the natural bounties these shores had to offer, they were also the first to deplete their target species. In 1792 the first sealers harvested a shipload of skins destined for China, but by 1820 the heyday of sealing had passed – the stocks were depleted below a commercially sustainable level.

In the mid-1800s it was the turn of the oyster beds to get a hammering. These sought-after bi-valves were easily transported across the Tasman as deck cargo. They needed minimal care – cover from the sun and regular sluicing with water. Hooked records many of the oyster beds around the country being quickly smashed over and destined to oblivion. It took just 14 years to denude Otago harbour of its beds…and so the story goes on…history repeating itself, just the name of the species and the locations changing.

“This leads me neatly to what recreational fishers want – and that is abundance.”

Grant Dixon

What I don’t understand is why we must fish our resources down to Maximum Sustainable Yield. To me, it is ecological brinksmanship based on science that may or may not be right. During the Cold War years that followed World War Two, the superpowers of the day brought our planet to the precipice of nuclear disaster. Similarly, in resource management terms, MSY allows a fishery to be screwed down to a very fine line between ‘just surviving’ and disaster.

International best practice says a fishery should be no less than 40 percent of the original biomass, so why does New Zealand not follow that recommendation?

Now to achieve that number puts all players between a rock and a hard place.

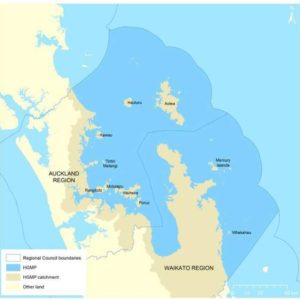

Let’s talk SNA1 here.

At a recent Working Group Meeting, the scientists advised now know more about the recreational extraction than the uncertainties associated with the harvest of that stock. The good news for us is that recent science points to a much smaller annual amateur take than first thought. So we have been saving ‘our’ allowance, but don’t think it is industry’s for the taking. We prefer to bank it with the future in mind.

A MPI scientist advised that it was important to know not only what was being retained (which was already being monitored in SNA1) but also the number of fish released and their subsequent survival. No valid self-reporting system had been successful anywhere else in the world. A self-reporting system would only be valid if there was 100% participation by all fishers. The costs would be prohibitive.

The Ministry has enough trouble getting the charter boats to comply, let alone every fisher who dangles a line. The recent large-scale surveys seem the best option, with a little tweaking here and there. It’s the old story – if you can’t measure it accurately, you can’t manage it effectively. Restrictions on bag limits, effort and an increase in the minimum size have been punches rec fishers have taken on the chin over many years. All but the most recent reductions have been voluntarily made.

To achieve the 40 percent rebuild will need the commercial sector to take cuts and that may mean job losses, reduction in income for the fishers themselves and a smaller dividend for the corporate’s shareholders. In the short term, share our pain. A move towards abundance will see the politicians come under pressure, the connection between political party leadership and the fisheries corporates being well documented.

But let’s think this through.

What does abundance mean for commercial interests? Yes – short term pain, but think of the gains.

If there are more fish out there, it will be easier to catch. Less effort means a reduction in costs.

There will be abundance over a variety of year classes so industry will be able to target specific sized fish for different markets with improved returns. There will be the opportunity to add value to various products, meaning more cash in hand. The value chain is burnt by depletion – in an abundant fishery the value of your product and the spin-offs from producing it will increase.

At present in some fisheries there is a disjoint between the science and observation. These two often describe very different worlds. Currently, the scientists tell us the Northern Kahawai fishery is at B52 or 52% of the original biomass. Yes, it is a healthy fishery, but anecdotal evidence while observing a stabilisation in fish stocks, does not show the increases the science is apparently telling us.

Abundance also offers us the opportunity to conserve fish. Recreational fishers have become more willing to bank fish for future generations, but not for increased exports. There have been few calls from the public to increase bag limits, nowadays its all about saving some for all our kids.

Another way to achieve abundance is the reduction of waste and I acknowledge the industry’s efforts in this direction with a variety of net styles and systems being successfully trialled by the likes of Sanfords and Aotearoa Fisheries. Long may it continue.

I always found it ironic that recreational fishers were prepared to fund research into commercial methods that reduced waste and were less damaging to the environment – I refer to the $35,000 given to kick-start Napier trawlerman Rick Birch’s work on diamond mesh – when the then Ministry of Fisheries and your own industry disowned it. To its credit, the recreational sector in the 23 years I have been involved with NZ Fishing News has pushed the ‘reduce waste’ message within its own ranks.

We have learned from industry about caring for the catch. Few anglers today put to sea without a decent bin and a bag or two of ice – a far cry from the wet sack in the scuppers approach I grew up with. Iki spikes are now on just about every boat I fish from.

‘Limit your catch, not catch your limit’ has been another war cry being promoted and there has been a real change in attitude to valuing breeding stock. It has been a long time since you saw a Big kill’ shot in the magazine. You only have to look at social media to see the comments when someone posts a pic of themselves or a mate with a trophy catch – ‘hope you put it back’ is a common response.

Other campaigns such as Matt Watson’s www.freefishheads.co.nz where there is a register of people willing to take the heads and frames of filleted fish shows a willingness to maximise the catch. There are several disparities between what recreational fishers can take in regard to fish size and seasons. Concessions have always been a grating point and always will.

The Coromandel Scallop regulations where industry gets a month’s head start and can take fish down to 90mm, whereas the recreational gatherers get to pick over what is left and can only take a 100mm sized shell sticks in our craw. Similarly, differences in Cray 3 regulations sees a situation which has severely reduced the ability of recreational fishers to catch legal crayfish and has been a festering sore for many years.

Various promises have been made, but not kept

Another recent example is in Cray 2 where despite the recreational catch collapsing from an allowance of 140 tonnes to less than 40 tonnes taken, there has been no provision made to improve this, although there is provision for an increase in the TACC. The fishery has not been managed for abundance, only to halt further decline. To my mind, that is not a way forward.

The Ministry has its hopes pinned on joint working group arrangements, but there are not many good stories to tell at this stage. The litmus test for me will be the SNA1 Joint Working Group. This was set up by the Ministry with representatives from commercial, customary and recreational interests and is chaired by Sir Ian Barker, an internationally recognised arbitration judge whose involvement should ensure transparency.

With access to considerable science, this group was challenged to come up with a strategic plan to manage SNA 1 – North Cape to East Cape. It is a fishery that is of great importance to recreational fishers and industry alike. There have been over 20 meetings in the last 18 months and although no result has been announced, MPI is hanging their hat on this as the best management method going forward.

Returning to the second part of my speaking brief, trust, it is fair to say there is a great deal of mistrust among all parties involved, not just between recreational and commercial interests. It is probably well founded as several recent documentaries on the state of our industry and the likes of joint-venture boats can attest.

Management processes are far from transparent and add to this the murky world of political and big business ties, and you have a breeding ground for discontent.

Recreational fishers see that they have to constantly carry the can disproportionately for the demise of many fisheries. They get the scraps of any deal – without going into the details, Marlborough Sounds cod is a prime example – with the importance of the mighty dollar being thrown in their faces.

That is all about to change, notwithstanding the fact that the Minister must consult and consider the social, economic and cultural well-being effects of any decisions he makes. The one thing that is going to have a major impact on the recreational stake around the bargaining table is the current study being undertaken as to the domestic economic value of the recreational fishery on the New Zealand economy.

Similar studies – by this reputable international company, Southwick Associates, and others – undertaken overseas, puts an extremely high value on the fish stocks caught recreationally, to the point some governments have made law changes in favour of recreational interests. I predict the same will ultimately happen here.

The Ministry commissioned a similar study a number of years ago but despite it passing peer review, was not accepted after industry kicked up a stink – obviously its findings were not to its liking! My good friend Mr. Collins describes trust as ‘to consign to care’ with other synonyms for trust being ‘guardianship’, protection’, ‘safe keeping’ and ‘having faith in’.

In the past commercial fishers were in almost every town dotted around our coastline. They were part of the community and were trusted as generally hard-working, honest people. They often shared their knowledge willingly with recreational fishers, but as more and more of the quota was soaked up by the corporates, these people were less evident in our community.

This came at a time when reductions in fish stocks impacted on recreational catch, and those commercial fishers left in the smaller communities probably bore the brunt of criticism for a situation which was mainly out of their control.

In the interest of fostering trust, through the magazine I am keen to produce a series of features on the various types of commercial fishing. I am not talking doing a snow job on readers in favour of one sector or another, but to highlight the issues the inshore fishers face, along with some tips and tricks from the professionals on how to improve recreational results.

Many of our problems are your problems. It will lead to a better understanding, I believe, of each other’s positions.

So how do we restore trust between all sectors?

I can only go back to that one word – abundance. If there is plenty of fish to go round, many areas of conflict will drift into insignificance. One thing we can all work together on which will be of mutual benefit and that is eliminating theft from the fishery. Kiwis have an innate sense of fairness. While we are not generally whistleblowers, we are quick to recognise when one group takes an unfair advantage over another by foul means.

The public is increasingly using the Ministry’s 0800 POACHER contact line and there have been some good results from its compliance officers as a result. When a member of the public is caught, the impact of the transgression is relatively small. When a commercial fisher gets it wrong, the effect is often measured in tonnes.

So there you have it, my personal thoughts on a fishery that one day I sincerely hope I can refer to as ‘shared’ in a trusting environment. We all need to fish for the future, not today.

Thank you for this opportunity, I look forward to further discussions over a beer and dinner – please don’t shoot the messenger!